IN CONVERSATION WITH DAVID GREGORY AND JAKE WEST

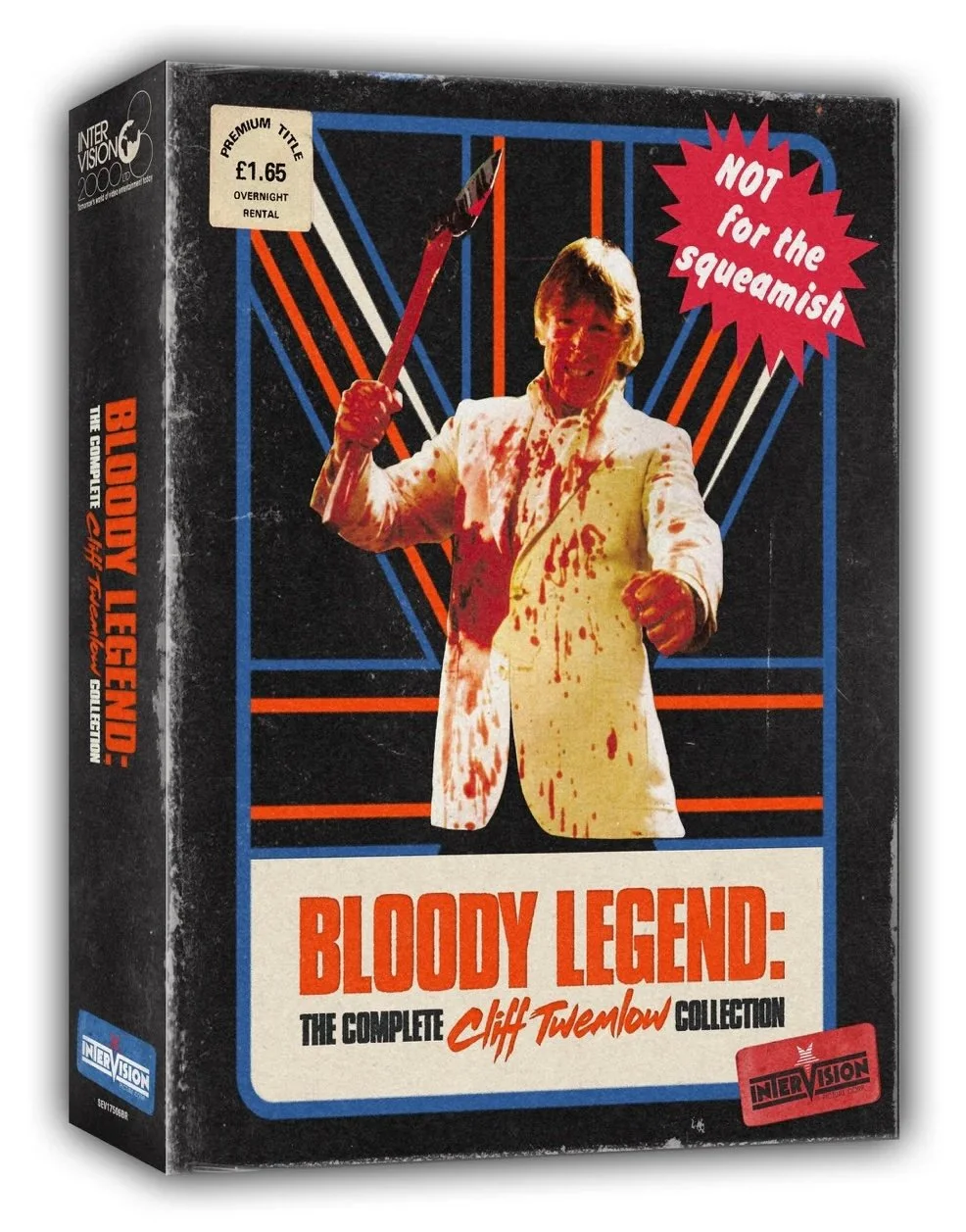

After a lengthy and acclaimed festival run, Jake West’s highly entertaining and affecting documentary MANCUNIAN MAN: THE LEGENDARY LIFE OF CLIFF TWEMLOW finally arrives on Blu-ray as part of the mammoth 9-disc boxset BLOODY LEGEND: THE COMPLETE CLIFF TWEMLOW COLLECTION. Collecting the complete works of the bouncer/novelist/screenwriter/actor and songwriter, this extensive collection comes packed with a wealth of extras that honour the legacy of one of genre cinema's forgotten heroes. Gore In The Store sat with director Jake West and producer David Gregory to discuss the much missed one man film industry, their affinity for his work and the disheartening state of the BBFC not giving the box set an actual release in the UK.

GORE IN THE STORE - So, a question for both of you is, how and when did you first come across Cliff Twemlow and his work?

DAVID GREGORY - Well, for me it was seeing G.B.H in the video shop in Gray's Video in Arnold in Nottingham, and seeing that cover of Cliff in the white tuxedo splattered in blood with what I couldn't even tell was an axe, I just knew it was a dangerous weapon. So that obviously leapt off the shelf to me as a young gorehound when I was probably about 11 or 12.

JAKE WEST - Once again, it was because it was caught up in the video nasties thing. It wasn't necessarily a film that looked to me like a straight horror film, despite the cover. If you looked at the back of the VHS box, it felt more like a kind of thriller type thing. So I wasn't quite sure what it was for quite a time, and when I saw it, because it was shot on video, it was quite different to most of the other stuff that had been caught up in the scare. So I saw it because it had been labelled a video nasty, rather than really knowing what it was. And I didn't know anything about Twemlow at that point at all.

How did the idea for the documentary come about, and who approached who about it?

DG - Well, it started because we were talking to Brian Sterling Vete about the rights to the movies, they'd been quite murky for some time. And Brian is the one who was untangling them and dealing with the various people from the Twemlow estate. I met with him the best part of ten years ago now. We decided we wanted G.B.H but then he was like, "Well, I've got all these other films as well." And I was like, "There’s other films?"

I knew about G.B.H. 2 and that a couple of other films existed, but I didn't know just how many there were. And then we started shooting some extras in Manchester and recorded some commentaries. David Flint and my partner, Carl, did some preliminary interviews, and David assembled that into a very rough thing. He didn't have the whole story. He got bits and pieces of the story, but I realised a real documentary actually needed to be made about this guy. This is something important. So that's when I call up my mate, Jake.

JW- It was me who assembled all the footage, because David originally said, I've shot a bunch of stuff for this Cliff Twemlow thing. I didn't know Cliff had done all these other films, I knew very little about Cliff's career at that point, obviously, other than G.B.H. and maybe FIRESTAR, those being the only ones that had really got a visible release. So David said, "We've been shooting stuff for a possible Twemlow kind of release. And oh, there's all these other movies as well." So he sent and asked me to put together all of the stuff that they shot thus far. I kind of assembled it, and was sort of eking out a framework for the story in a very rough way. I sent it back to David, and that's when he came back to me and said, "You've done a really nice job assembling this stuff. As a filmmaker, would you be interested in taking this on?” I said to David, well, as long as you're not in any rush, because I was finishing off Midnight Peep Show at that time, which was an anthology and because I needed to really research Cliff and find out all about him. And that's when I got the brilliant book, The Lost World of Cliff Twemlow by C. P. Lee, who we'd interviewed for the Video Nasties set. And I remembered, when I went back to looking at that interview with the rushes that we'd done, he was talking about these other films that Cliff had done. Well, what are all these films? That was my beginning of the Cliff journey. But it was such an intriguing and really interesting thing, the little snippets of stuff that David had already found.

DG - Basically, the way it was assembled, there were so many tantalising bits and pieces there. But because we've both done a lot of feature documentaries, it was like, okay, there's big chunks of the story missing here, and there's people that keep on getting mentioned that we haven't got here. And so that's when it was decided to actually be given a proper production. It can't actually just be a series of interviews and hope that it all fits together. And that's where Jake came in and took over.

JW - What was appealing about the story, and I think it's very much evident when people watch it, is we had these first tantalising glimpses of all these people talking about Cliff with a lot of love, but also talking about what a disaster most of his productions were! So there was this inherently interesting story arc to all of this stuff. It felt like there was more there and a bigger story to tell. That was something that excited me and David, and as we progressed, we couldn't quite believe the amazing things we were uncovering about what happened to Cliff. The more people we spoke to, the more the excavation continued.

DG - Yeah, and that's when we started finding bits of films and Marc Morris, Jake's partner, somebody I've been buying videos off since before I was a teenager, he's basically, as Jake refers to him, the Sherlock Holmes of home video. He was finding bits and pieces from all over Europe to actually not just put in the documentary, but then find better elements for the box set.

JW - A lot of people will know Marc, because of the Video Nasties set, he's been involved in the Video Nasties world forever, and he's one of the most knowledgeable people about that whole area. So, having him finding all the amazing clips and stuff and finding the masters along with a big, solid team of people who really knew what they were looking at and for, it was a really interesting period of discovery. We were unearthing Twemlow stuff that nobody had seen for at least forty years, and in some cases, forever!

So, when did you actually start on the project, David? Was that about 10 years ago?

DG – The best part of ten years ago. That's when I first met Brian. We didn't start shooting the interviews right away. But I don't want to downplay just how important it was that Jake took over with the documentary, because that's when it really became something that we could all envision. It wasn't just kind of like, “Oh, look at these unheard of movies that we've found.” There's nothing wrong with that, but, there's a true story here of an entire stock company, of people who were around this and all the best no budget filmmakers have their friends and and experts in certain areas who, when you pick up the phone and say "Okay, we're shooting on Saturday" are just willing to show up with their area of expertise. And in a lot of cases with Cliff, it was bouncers and martial artists and glamorous women. So they were trying to make James Bond movies in the back streets of Manchester.

Like you've just said, the film is not just about one thing; it goes down so many other avenues. Did you find yourselves being a bit overwhelmed by all the stories that you discovered about Cliff and all of these other people and all their adventures?

JW - Well, it's one of those things where there were so many stories. You've got such a wealth of material, it's really about just whittling it down to a more manageable length, which is going to work as a documentary, because we were looking at all of his career and every film he had made over a period of about nearly 20 years. We also look at his early life as well, so there was a lot to pack in. What was great was hearing all these amazing stories. And every time we found a new person to talk to, we got another point of view on the story. But like a lot of documentaries, what you find out as you're going along is you're continually trying things out and replacing things, and it gets longer and longer, and then you gotta go, well, what's the stuff we love? There was some stuff where we binned some things, and then we went, actually, that was really good, we'll put it back in. But for people who want to see a bit more of the slightly longer version of this, on the new release, there's over an hour of deleted stuff, which, it wasn't so much deleted stuff, it just was stuff that wasn't going to work at that length.

So, there’s stuff that was removed at an earlier point, but there's an extra hour of the documentary that you can see, which is all really fascinating as well. But if that was in the main piece, it would have been too slow. So it was important to really get the pace right. And I think that's something that David was very good at working on, helping get the shape of the documentary right, which was really important.

DG - Yeah, it was a real creative pleasure to bounce off each other, because Jake and I have both directed films like this. Because he was deeply in the edit, he would show me a cut, and it was easy for me to say, you know, I don't think we need this, or maybe this should go there. And rather than being precious about everything, it was actually a really good kind of bouncing back and forth. So it was very enjoyable.

JW - Because this documentary is such a big beast in terms of the time frame that we were covering, sometimes I would be in the edit, just trying stuff out. And when I had a sequence, I would show David. It was really about getting the structure right, to get all of the information in the right shape, because we were following a chronology of his life, but we were also trying to build some themes into it, about how there were reoccurring problems that he had, but also to keep it entertaining and hopefully a bit poignant as well. So you're working on different levels of the edit when you're really kind of in depth on it, but that's the fun of this kind of filmmaking.

Was this any more of a challenge than your other documentaries that you've both done?

DG - For me? No, because I got the easy side of it. I got to see the cuts when they arrived, and I could take a step back, and see in a sort of bigger picture way that Jake couldn't necessarily have, having been immersed in it for weeks before delivering the cut. It was a long ride. And a lot of finessing had to go on, but it certainly wasn't difficult.

JW - When you're making a documentary, from a director point of view, what you're really trying to do is just trying to understand the story that you're trying to tell, trying to give it something which is just more than just people's recollections. So we wanted to feel it had a narrative, but in a way, the narrative is created by the people telling their story. There's no voiceover or anything like that. Shaping that kind of edit is more just a continual sort of finessing. Each documentary has its own challenge, but as the maker of the documentary, you're trying to find what the story is in your own mind first. We've created a story that is very much about somebody trying to overcome the odds. And maybe not being a talented director, but certainly being one with the most enthusiasm for what he did.

DG – And after he didn't overcome the odds, he bounced back, and kept on coming back.

JW - That's kind of what made it fun. And you could get this feeling that he's going to succeed this time. It was an enjoyable ride, and it was just really learning about Cliff that made that possible. Because the more I found out about him, the more enabled I was to make it better.

Make it stand out

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

When you discovered all of these other films that you didn't know about previously, did you, in your research and going through his archives, come across any unmade projects that you think you could have taken Cliff to the next level, career-wise?

DG – I don't know about that, but he definitely kept on starting new films before the previous one was finished. And in some cases, he would abandon them after just doing the promo. But why don't you talk about the one that you actually were able to kind of sort of reassemble, Jake?

JW - Probably the most interesting artefact, which falls into that category that you mentioned, was a project called TOKYO SUNRISE. Cliff shot that in around 1987 or ‘88 and he shot it to originally make a promo which he was going to take to Cannes. And he did take it there, in fact. This was a project where he had only shot for four days, and he ended up creating a two minute promo, which is on the boxset as well. But it meant that they had actually shot a number of scenes from this. He had a full script that he had written, but he didn't have the finances to make it, but he shot for four days, and we managed to unearth the rushes tape for that. There was about 16 or 17 Beta SP rushes tapes. So it meant that I could go back to his original script and assemble all of the scenes as they were written originally, and put them in chronological order. So you've got a quarter of a Cliff Twemlow film, twenty minutes of TOKYO SUNRISE instead of two minutes.

It's a really interesting thing. Cliff always sort of fell down a bit in post production, because he never really had a solid handle on editing. And David Kent-Watson (Twemlow's regular director), that wasn't really his skill either. So this is probably the most tightly edited piece of Cliff's work. You can see, perhaps, what Cliff's work might have been like if he had managed to work with somebody who'd been better at post production. And when we're showing it to people, they've loved this piece. We premiered it at the Manchester Festival of Fantastic Films just recently, and that's the first time it's been shown. So everyone else is going to see it when it comes out. It's a really interesting, tantalizing glimpse of a Cliff film which almost was.

David, as you mentioned there, Cliff was getting the idea for the next film before finishing the current one he was on. So he was obviously an ideas man. Do you think he had too many ideas?

DG – Well, that was one of the things that attracted us to this story, in particular to make it into a feature documentary. It is entirely unique to have a bouncer dreaming of becoming a Hollywood filmmaker and wanting to do it in Manchester. I can't think of any other stories that are quite like that. There's plenty of people who grow up wanting to be filmmakers, whereas he was going to be a bouncer or a writer or a singer. I mean he just was full of ideas, but he couldn't actually quite make them all gel at the same time in such a way that he could move forward. So he always kind of stayed in this area. I think there's something actually quite admirable about that. He's quite a dreamer, in terms of "I'm not going to be limited by my circumstances. I'm going for gold." And even if he didn't quite make it, there is something to be said about him.

Just listen to the people who worked with him, how much they loved this guy, and how much they loved working with him and would do anything for him while rarely getting paid, and certainly not getting paid sufficiently. And in the end they did get some films out there. Today, it's hard to make a film, even a very low budget, quick film. So as you'll see in the box set there's a lot of films that did get completed. They just never got distribution. They may have gotten them to the finish line, and they were like, “Okay, let's move on to the next one. Let's not worry about the distribution.”

JW - Cliff was also very kind of forward thinking, in the sense that he was the right man at the right time, because he recognized the emergence of home video as a way to move forward as an independent kind of producer filmmaker, because the technology was there and because he couldn't afford to do bigger budget films. He got the film bug because he actually starred in a film. He was one of the supporting characters in a film called TUXEDO WARRIOR, a film which was allegedly based on his own autobiography about his time as a bouncer. But the film was completely different. It was set in Africa, and it had nothing to do with clubs in Manchester, but the producers loved the title, so they bought and licensed the material off him, and they essentially bought the name.

He got invited to go on to this film, and he acted in it, and in that film, which was a proper production shot on 35 mm, Cliff is being directed by somebody else who knows what they're doing. He's actually a better actor, and he's better in a smaller part, funnily enough. But Cliff, obviously, wanted to make himself a star. He had this dream of writing the theme song, singing the theme song, and doing the acting, almost biting off more than he could chew. But what enabled him to do that was this interesting moment in technology, because he realized that he could shoot feature films on video and release them on tape. So that was his kind of workaround of having to come up with huge budgets, which even smaller independent films needed at that time. So he was one of the earliest components of straight to video stuff. I mean, there's a few. There was SUFFER THE LITTLE CHILDREN as well. Wasn't there David?

DG - That's right. There were a couple of British ones, but I think G.B.H was the first to get a wide release, and certainly to actually have some level of success.

JW - And that marked Cliff out as somebody different. In his career, he generally followed this path of shooting on video, and that was something that kind of defined the look of his films with the exception of his werewolf film, MOONSTALKER, and that was where he went back to shooting on 16 mm. And that film obviously looks a lot nicer, shot on 16 mm by a very young David Tattershall who went on to film THE GREEN MILE, and the STAR WARS prequels. At that time David was just a very young man, I think it was his first job as the main DP, but that film looks so much nicer because it's shot properly, but once again, unfortunately, Cliff had problems getting that distributed. It's actually a film which looks very nice, so you can see these glimpses of what might have happened if he had had more success and got more money, and it's a shame he never got it. Where most directors end up going up in budget, Cliff was kind of going down in budget. So at the end of his career, he was literally making stuff at the weekend on IA for like 50 quid.

As a writer, novelist, songwriter, actor, do you think he could have been an influence on a certain GARTH MARENGHI'S DARKPLACE?

DG - I don't know if it's a conscious influence but it could be worth asking Matthew Holness that, because certainly THE BEAST OF KANE and THE PIKE are definitely in that school of pulp horror fiction from that era. But he only made one outright horror film, EYE OF SATAN, but there's certainly a similarity, although I don't think he was quite as pretentious as Garth Marenghi!

JW - I think the thing with Garth Marenghi, is there’s definitely that kind of 70s pulp novel thing. I mean the kind of books that Garth writes are a bit more Shaun Hutson-esque in terms of that. But I think it's interesting, and it definitely would be worth asking, actually, because I suppose the idea that, you know, with GARTH MARENGHI'S DARKPLACE, that he is also the actor and the star. And maybe there is something there., I don't know what is, you know, we would have to ask Matthew about that at some point. That'd be interesting to find out!

With this and the VIDEO NASTIES documentaries, you've really examined in-depth, the UK genre scene and the state of it at that time and place. Why do you think it has become such fertile ground for all these kinds of stories?

DG - I didn't even realize it, but I got so incensed as an 11 or 12 year old that this stuff was being taken away from me. It just became like this disproportionate pattern of, ”Why are they taking these films away from me? I am now determined to see every single one of these films.” Before I was buying tapes. Now I'm buying rights and actually doing documentaries about the films or the era or things like that. And it seems like that's just never going to end. So thank you, Mary Whitehouse, you pretty much set me on my path for life, whether I knew it or not.

JW - It would be interesting to see in a sort of alternate reality, where, if there had been a more kind of liberal leaning authority there could have been no video nasties. And if that could have been,. we would have been bereft of a whole bunch of filmmakers that exist because of the nasties scare. So in some ways James Ferman and Mary Whitehouse were kind of midwives to the next generation.

DG - They were the Devil’s Midwives!

JW - And they never realised that! It backfired on them. And I think that's something. It backfires because standards always change down the line. And what was offensive, you know, in the sixties or fifties is then acceptable in the seventies or eighties.

DG - And laughable in a lot of cases, really this was censored!

JW - But the thing is the audience are always ahead of the censors. In that sense, they're like, “Well, why are they doing this?” But back then, we were at a point where there was still a sort of class system in the UK, and people like Ferman were very snobby about what he felt that certain people could watch. And that is usually what caused that incensed feeling of there's something wrong with these decisions.

How do you feel that the boxset isn't getting a physical release in the UK because of what is basically an outdated law, where basically every single film and every single special feature and subtitle must be pored over and paid for by the submitting company, that the BBFC still somehow insists upon?

DG - The fact is, the BBFC still has this ridiculous monopoly over the physical media industry. It's not even the digital platforms. It's just physical, and physical is struggling as it is, and they're basically nailing an extra nail into the coffin of physical media for companies like us, because it's just cost prohibitive to get a sensitive certificate, a BBFC certificate for all of these movies. So basically, we're making it available in the UK, through the US, as you can with anything these days. You couldn't do that back in the eighties. But now you know, you can pretty much buy anything, as long as what's on it isn't illegal. There are other laws that cover that. But the fact is, as Severin, we're quite proud to actually import that into the UK, because it is a British story, and it's a British story that should be seen, and unfortunately, it's being repressed by the BBFC’s draconian laws.

JW - It's just one of those really kind of unfortunate things, because it's no longer a case of these films getting into trouble with any censorship. It's more just the BBFC charges so much money, and there's so much material on the set, and there's so many films, and it's unfortunate. Cliff Twemlow is not a mainstream guy, like Steven Spielberg. This is not going to sell millions and millions of copies. It's something which is a niche, and this is the problem why it makes something like this cost prohibitive, because of the volume of material that has to be classified by the BBFC. I mean, we know that the whole set will be an 18. We could just give it an 18. There's nothing in there that's going to get censored. But this is the problem with the BBFC. To get that 18, we have to have a lot of money; we can't just go “Oh, this is all stuff from the eighties and the nineties, no one's going to be offended by this anymore. Just give it an 18.” But you can't do that. At some point, maybe censorship will change. But they always want to be able to make money, and that's what they're doing these days.

Iain MacLeod

BLOODY LEGEND: THE COMPLETE CLIFF TWEMLOW COLLECTION is released on the 29th July by Intervision and is available to order through www.severinfilms.com. MANCUNIAN MAN: THE LEGENDARY LIFE OF CLIFF TWEMLOW and several of Cliff’s films will also be available to stream through Amazon Prime.